A few days ago, a famous tech CEO said that AI models already have access to close to all possible existing human-generated data for training. To me, that seems a preposterous idea.

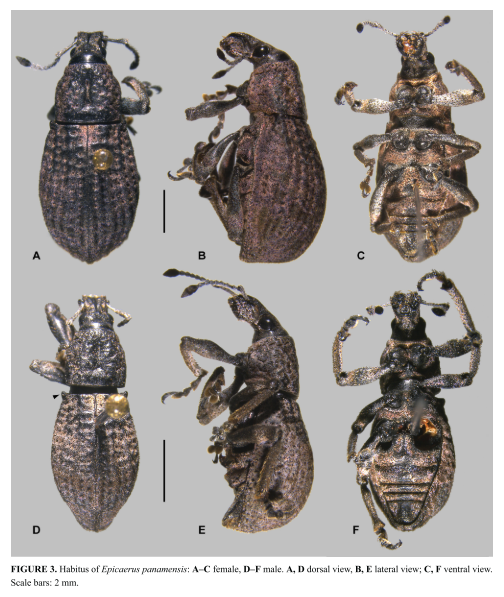

I work with organisms that have thousands of species and absolutely no digital presence. No photos from collection specimens. No digitized data. No papers in digital format or that have been scanned. No mentions anywhere in the internet. Not a single image ever taken. NADA.

However, these animals do exist. They pollinate plants we care about; they eat plants we care about. They may even be extremely abundant if one knows where to look for them. However, almost no one in the world would be able to know they saw one of these species, since almost no one has access to their information. This is human-generated data that is completely inaccessible to other humans, and to machines.

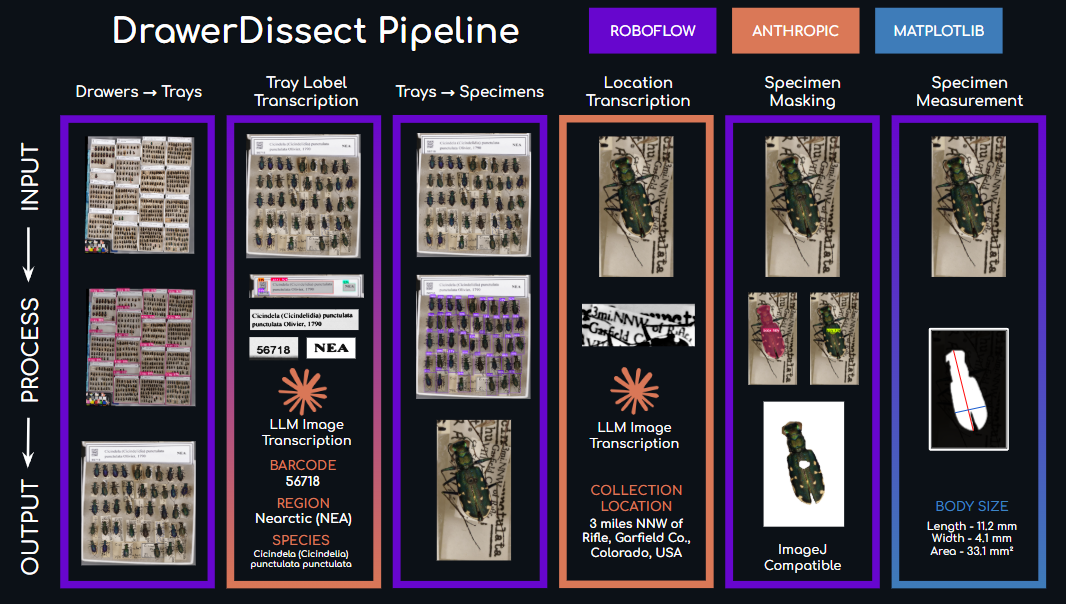

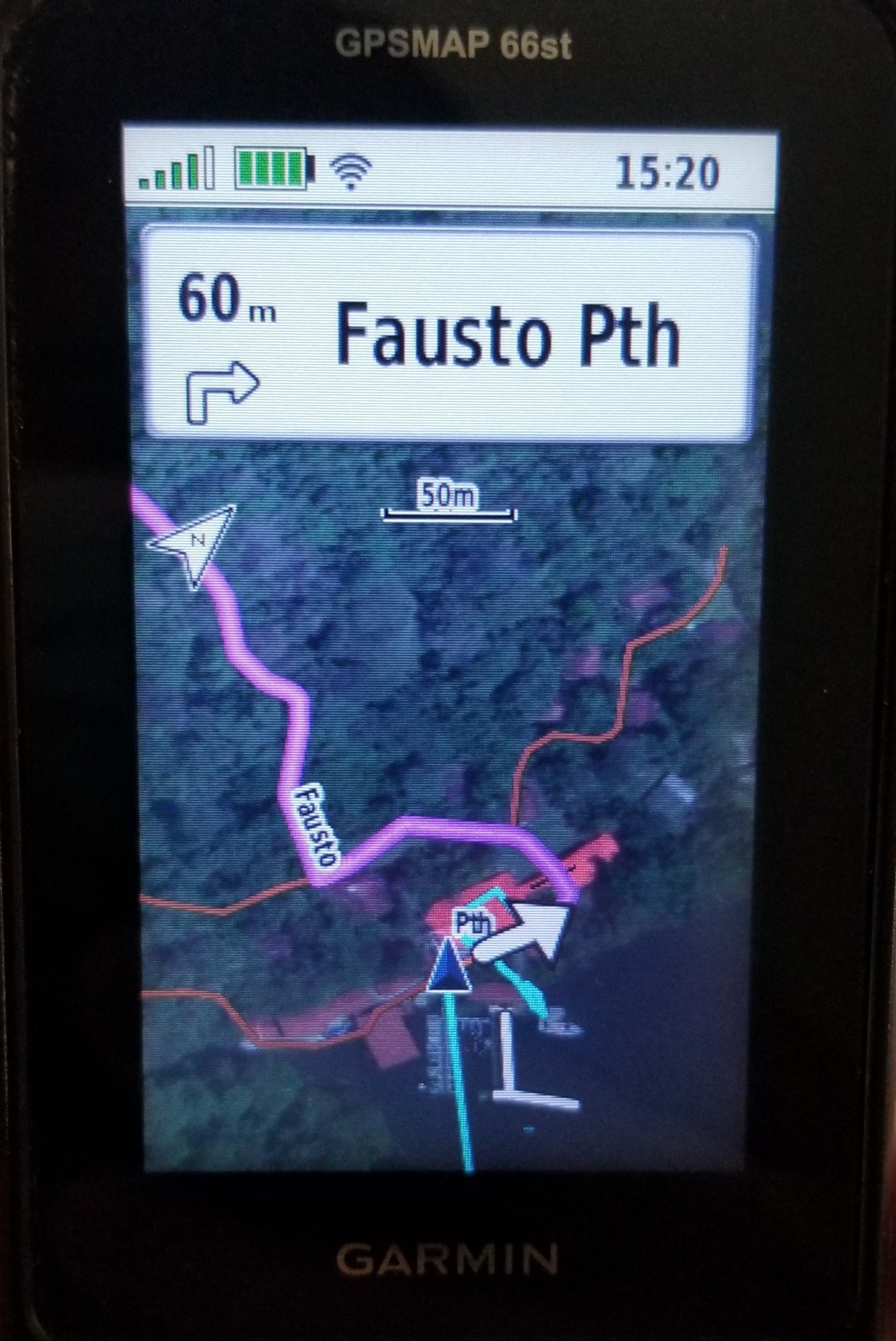

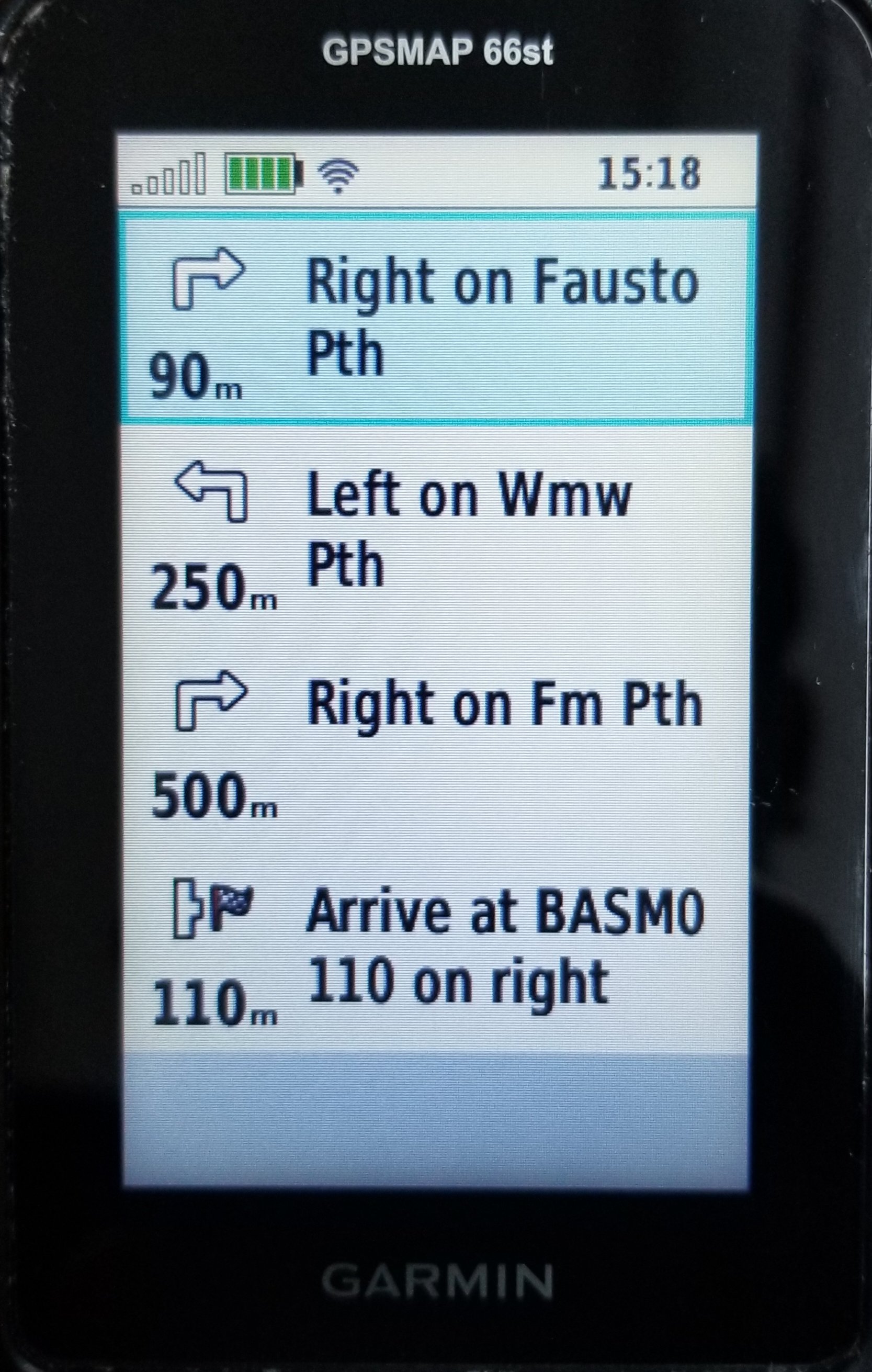

If we want to improve the ways in which we document biodiversity, we need to change that. About 2 years ago, we started a project in the Field Museum to quickly photograph and digitize the easiest data about our specimens: what they look like and what they are called. Dry entomological collections are often organized by taxonomy, so we do not need to read the labels under the specimens to know their species name. And we can easily get a dorsal photo of many specimens at once by scanning them with machines such as a GIGAmacro.

A lot of people have been more focused on the data under the specimens, written in their labels, which can also be very useful. The number of specimens for which we have that kind of data is many orders of magnitude bigger than the specimens that have been imaged so far. So finding a way to image them fast is actually a very good complement to these efforts.

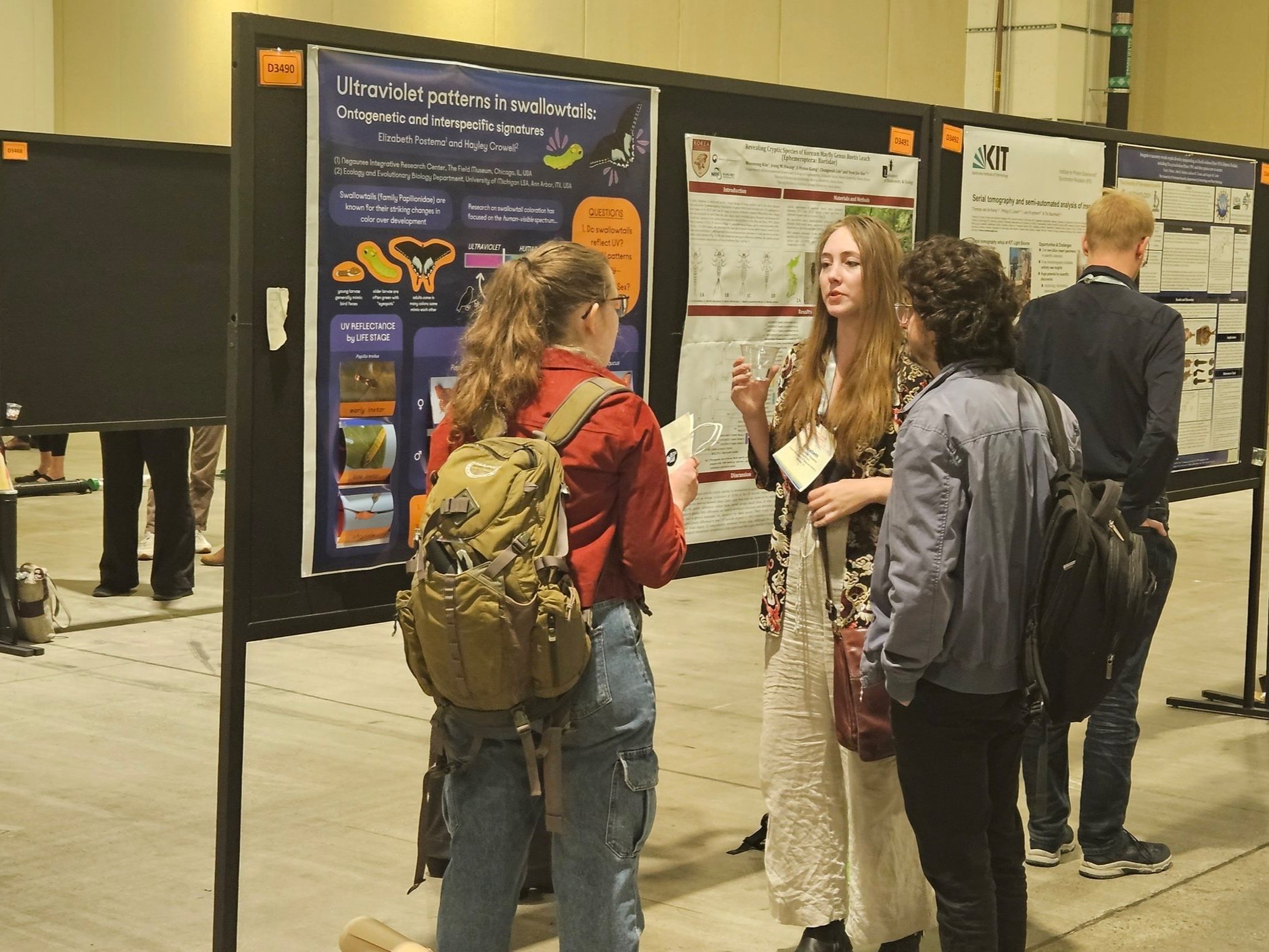

We just released the software we developed, and wrote a preprint explaining how it works. It heavily uses Roboflow, a platform that was as excited about this work as we were. We show how we used that software to image a whole family of beetles at the Field Museum collection in 2 weeks, and gave a glimpse of what one can learn from this kind of data. We created an image classification model that is good a detecting tiger beetle species and subspecies, and we studied how beetle color changes through space. This effort has been led by postdoc Elizabeth Postema, who managed a team including from high school interns to collection managers to develop the tool and write up the preprint (all of them authors in the paper!). We dubbed this tools DrawerDissect, and we are hopeful it will be useful for the broader community!

We also got a great help from Roboflow, who provided us with the interface that we needed to engage interns and volunteers into preparing training sets for machine learning, even with no coding experience.

GitHub repo link: https://github.com/EGPostema/DrawerDissect

Preprint: Postema EG, Briscoe L, Harder C, Hancock GRA, Guarnieri LD, Fischer N, Johnson C, Souza D, Phillip D, Baquiran R, Sepulveda T, Medeiros BAS de (2025) DrawerDissect: Whole-drawer insect imaging, segmentation, and transcription using AI. EcoEvoRxiv, https://doi.org/10.32942/X2QW84